Gallipoli – An Irish Graveyard

Part 1 – Land Operations – the Regular Battalions

By Mal Murray – Gallipoli Association Forum Manager

Cover image: Members of the Royal Naval Division charging from their positions at Gallipoli. (World War I Illustrated)

Much debate and many pages have been written about Ireland’s involvement in the Great War. Mention of the war in Ireland is certain to focus on two significant events, the Easter Rising and the Battle of the Somme. Both events have, over time, been taken as representative of Ireland during the war. Here in Ireland both events have overshadowed a previous campaign; the Gallipoli Campaign of 1915-16.

The Gallipoli Campaign is seen in Australia and New Zealand as a defining moment in the history of their respective nations. The Irish involvement has all but been forgotten for many reasons. The decade 1913 to 1923 could be considered to be the most decisive and yet divisive decade in Irish history, and it is within this perspective that the Irish involvement in the Gallipoli Campaign should be considered.

In January 1919, Canon Charles O’Neill (Parish Priest of Kilcoo, Co. Down) attended the first sitting of Dáil Éireann. During the sitting the names of the men who had been elected during the General Election of 1918 were read out, but many were absent. For those absent their names were answered by the reply ‘faoi ghlas ag na Gaill’ meaning ‘locked up by the foreigner’. This had such an effect on him that some time afterwards he wrote the song ‘The Foggy Dew’. The song was written to tell the story of the Easter Rising but also attempted to show that Irishmen who fought for Britain during the war should have stayed home and fought for independence. It’s most significant elements with regards to this must be the following lines:

‘Twas better to die ‘neath an Irish sky than at Suvla or Sudh el Bahr’

How many who were taught that song, or indeed sing it, know where Suvla or Sud el Bahr are located or indeed their significance? These names were at the time on the lips of families all around the country and would leave deep scars and have a great effect on Irish attitudes towards the war. As Katherine Tynan wrote in 1919 in The Years of the Shadow: ‘So many of our friends had gone out in the 10th Division to perish at Suvla. For the first time came bitterness, for we felt that their lives had been thrown away and that their heroism had gone unrecognised. Suvla the burning beach, and the poisoned wells, and the blazing scrub, does not bear thinking on’.

Early Naval Operations in the Dardanelles

By late 1914 it was obvious all across Europe that the war on the Western Front for all intents and purposes had reached a stalemate. In attempting to break the deadlock new strategies were being reviewed. In January 1915, the Russians who were under great pressure on three fronts from the Germans, Austrians and Ottoman Empire requested that their allies (Great Britain and France) would conduct operations to divert attention away from them. The British First Lord of the Admiralty, Winston Churchill, conceived a strategy which would, it was hoped, divert enemy attention and resources away from the Russians. The plan was to force a passage through the Dardanelles Straits with a force of battleships and level their guns on Turkey’s capital, Constantinople. The Dardanelles is a narrow strait in northwestern Turkey connecting the Aegean Sea to the Sea of Marmara. It was believed that the arrival of such a force at Constantinople would force the Ottoman Empire out of the war. It was also believed that by taking the Ottoman’s out of the war a new flank could be opened along with the opening of a two way all year round supply route between Russia and her allies.

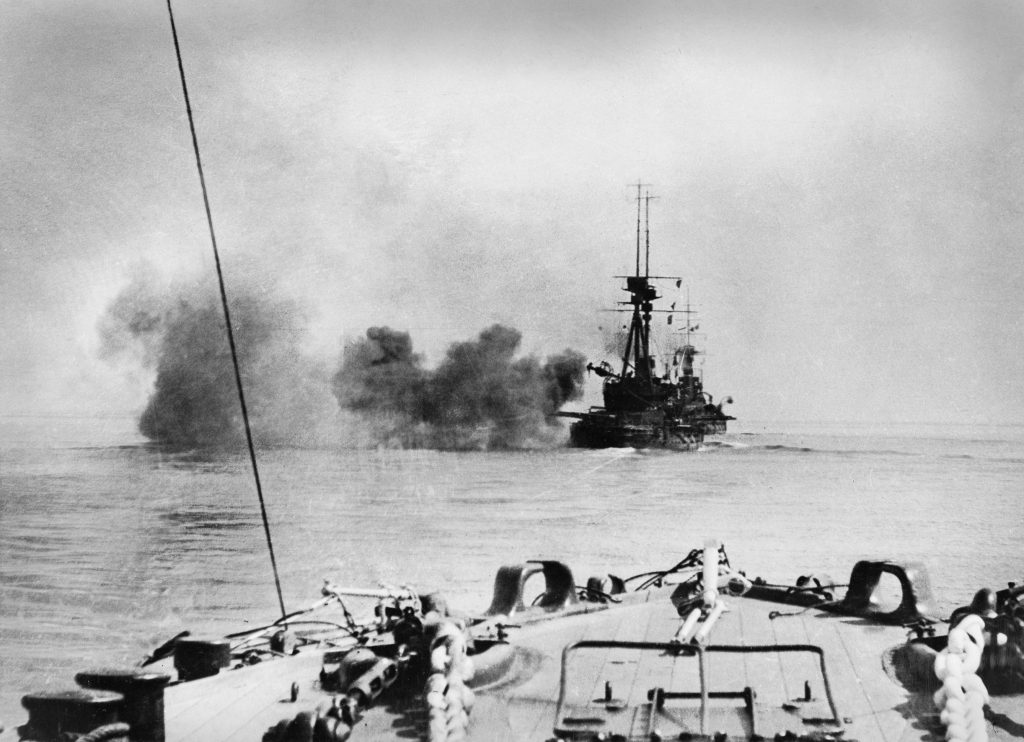

The Dardanelles had been the subject of a Royal Navy blockade since late 1914. It was now envisaged that this naval force re-enforced by other ships would force the Dardanelles and complete the mission. Between February and March 1915, naval operations were conducted against the Turkish fortifications in the straits by the Royal Navy supported by the French Navy and elements of the Royal Naval Division. On 18 March, a major naval assault on the straits failed with three ships sunk and three badly damaged. At this time it was decided that the straits could not be forced with a naval only operation and that land based operations must be conducted in conjunction with naval operations.

The Gallipoli Campaign – Planning

Following the failure of the naval assault General Sir Ian Hamilton was tasked by Lord Kitchener to act in support of the naval operations. It was decided that in order to force the straits the Gallipoli Peninsula would have to be taken. Under Hamilton, the Mediterranean Expeditionary Force (MEF) was tasked with the operation. Hamilton had a mixed command which included the 29th Division (consisting of three Regular Army Irish Regiments: 1st Battalion Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers, 1st Battalion Royal Munster Fusiliers and 1st Battalion Royal Dublin Fusiliers), the Royal Naval Division, the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps (ANZAC, consisting of the 1st Australian Division and the New Zealand Australian Division (New Zealand Infantry Brigade and 4th Australian Brigade)) and the French Oriental Expeditionary Corps (initially one Division but subsequently re-enforced with a second Division). Irish born soldiers would play a part at all levels within all of these contingents (French included) and the Gallipoli Campaign is as much their story as any other nations.

With short notice and limited resources General Hamilton made plans for landings on the Gallipoli Peninsula. This required reorganisation of the 29th Division transports to facilitate the conduct of efficient military operations. In order to prevent the Turkish fortifying the position, the date for the Allied offensive operations were set for mid-April.

The Gallipoli Campaign – April Landings

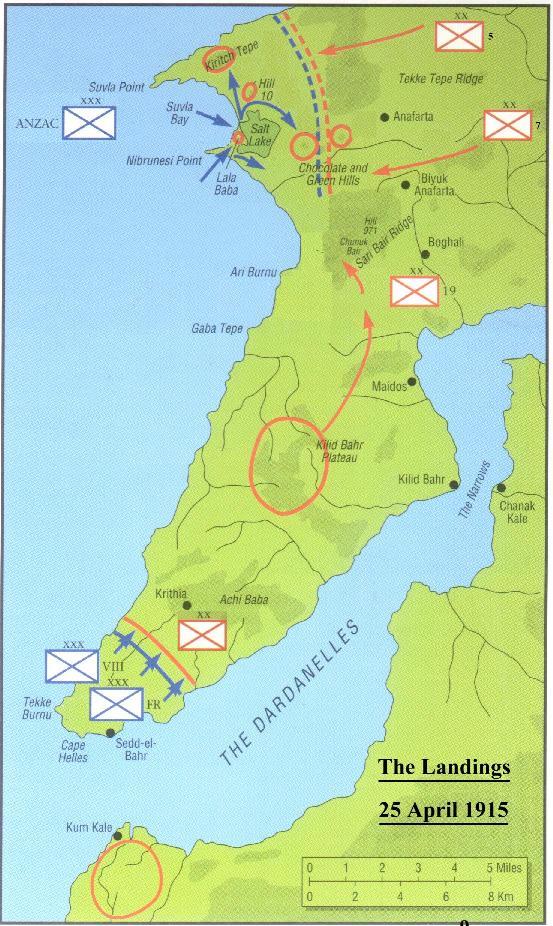

On 25 April 1915, the main assault took place. The strategic objectives were to secure the Achi Baba heights in order to dominate the straits. The British component landed at Cape Helles while ANZAC forces landed at Ari Burnu. These assaults were supported by a diversionary attack at Kum Kale on the Asian side of the Straits by the French. At Cape Helles the operational area assigned to 29th Division, were five beaches from east (inside the straits) to west (on the Aegean coast); S, V, W, X and Y. V and W beaches were the main landings at the tip of the Gallipoli Peninsula, either side of Cape Helles. On land the Ottoman Fifth Army: comprising two army Corps; the III Corps which defended the Gallipoli Peninsula and the XV Corps which defended the Asian shore, the 5th Division was positioned north of the peninsula under the command of First Army, and the Dardanelles Fortified Area Command.

For the purpose of this article the main focus must be centred on V Beach at the southern tip of the peninsula. V Beach has been described as a natural amphitheatre. The beach was approx 300 yards (270 m) long and 10 yards (9.1 m) wide, with a low bank about 5 feet (1.5 m) high on the landward side. Cape Helles and Fort Etrugrul (Fort No. 1) were on the left and the old Sedd el Bahr castle (Fort No. 3) was on the right looking from the sea and Hill 141 was inland. The beach had been wired and was defended by about a company of men from the 3rd Battalion 26th Regiment. Much debate has gone on since the landings as to whether the Turkish defenders where equipped with machine guns, the official history of the campaign (Military Operations Gallipoli: Inception of the Campaign to May 1915. Aspinall-Oglander) reports that they were equipped with four Maxim Machine Guns. The task of landing and securing the area was assigned to the Royal Munster Fusiliers and Royal Dublin Fusiliers (both part of 86th Infantry Brigade 29th Division). They were supported by two companies of 2nd Battalion Hampshire Regiment (88th Infantry Brigade 29th Division) and elements of the Royal Naval Air Service Armoured Car Division acting as fire support. Other elements including naval fire also supported the landings.

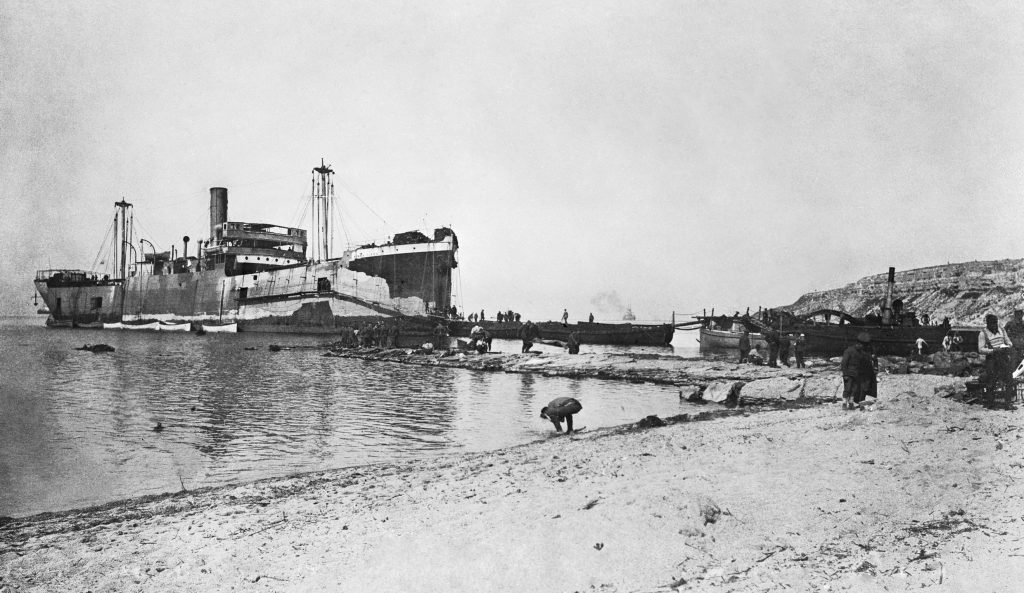

In order to accomplish the task, the assaulting troops were allocated the Collier ship SS River Clyde. The ship had been converted into an ad hoc amphibious assault ship and was referred to at the time as the ‘Trojan Horse’ of the campaign. It was under the command of Commander Edwin Unwin Royal Navy; it was his idea to use the vessel for this role. The Clyde was to be filled with troops and run aground at V Beach. Sally ports were cut through the steel plates in her sides so troops could emerge on to gangways supported by ropes which ran along the sides towards the bows of the vessel from each side. These gangways then led down to two barges which were to form a gangway to shore. The plan was for three boats containing three companies of Royal Dublin Fusiliers to land on the beach and secures the beach for supporting landings from the Clyde when she was deliberately beached.

Disposition of troops:

- Three companies of 1st Battalion Royal Dublin Fusiliers in boats

On board SS River Clyde:

- No. 1 Hold (upper deck).

- X, Y and Z companies, Royal Munster Fusiliers

- No. 1 Hold (lower deck)

- W Company Royal Munster Fusiliers

- W Company Royal Dublin Fusiliers

- No. 2 Hold

- Two companies Hampshire Regiment

- One company West Riding Field Engineers

- No. 3 and 4 Holds

- Two sub-divisions Field Ambulance.

- One platoon Anson Battalion Royal Naval Division

- One signal section

All the troops aboard the Clyde were under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Carrington Smith, Hampshire Regiment. Smith was killed in action during the landings and is named in the Irish Memorial Records.

Problems from the start

From the very start things went wrong. The boats containing the three companies from the Dublin Fusiliers were delayed by currents and came in thirty minutes late at 6:30am. The Turkish defenders opened fire just as the boats were landing. Guns in the fort and castle enfiladed the beach and killed many of the men in the boats, some of which were reported to have drifted away with no survivors. Many more casualties were suffered as the soldiers waded ashore and some wounded men drowned under the weight of their 60-pound packs. The survivors found shelter under the bank on the far side of the beach but most of the landing boats remained grounded with their crews dead around them. Two platoons landed intact on the right flank at the Camber and some troops reached the village, only to be overrun.

The SS River Clyde carrying the supporting troops had to slow down to avoid the boats containing the Dublin Fusiliers and therefore had not got the required speed to land high on the beach where it was originally intended (She would remain there throughout the campaign until re-floated in 1919). Because of this and the problems experienced by the Dublin Fusiliers, the boats which were to be used as pontoons to allow troops from the ship to disembark were not in position. Commander Unwin and members of his crew got into the water in the midst of the battle and attempted to form a bridge and assist some of the wounded. Six of them would receive the Victoria Cross for their actions that day.

Only the words of those who were there can truly describe what they experienced on the beach.

‘When my turn came I was wiser than my comrades. The moment I stood on the gangway, I jumped over the rope and on to the pontoon. Two more did the same, and I was already flat on the bridge. Those two chaps were at each side of me, but not for long, as the shrapnel was bursting all around. I was talking to the chap on my left when I saw a lump of lead enter his temple. I turned to the chap on my right, his name was Fitzgerald from Cork, but soon he was over the border. The one piece of shrapnel had done the job for two of them’

Private Timothy Buckley, 1st Battalion Royal Munster Fusiliers

An article in the Leinster Leader on 7 August 1915, gave this account from Private William Harris, 1st Battalion Royal Dublin Fusiliers:

‘On April 25th, before we got within 200 yards of the shore, we were under the heaviest shell and rifle fire that was ever known in the history of the war. When we came within 25 or 30 yards of the shore, our boats stopped. There was nothing for it only to swim ashore. Some got out all right, others were wounded and some never came out and may God rest them. It was only by chance anyone got out, for whichever way you swam that day you faced death. I will never forget when we got on land that morning at 5:30am in our wet clothes. Byrne and I, a chap named Keegan from Dublin and our officer were the only ones left of our platoon. We fell on our hands and faces and dared not move from that position for if we put up a finger we were shot. We lay there for 13 hours and I saw some of our brave friends, the Munsters, alongside me blown to pieces – heads, arms and everything off. Byrne was right behind me, his head touching my boots, yet near as I was I was afraid to twist my head to see if he was alive. The officer and Byrne got wounded later, I think I am the only member of the platoon who was not, but thank God’

‘The Dublin’s set off in open boats to their landing place which was the same as ours. As each boat got near the shore snipers shot down the oarsmen. The boats then began to drift and machine gun fire was turned onto them. You could see the men dropping everywhere and of the first boatload of 40 men, only 3 reached the shore all wounded. At the same time we ran the old collier onto the shore, but the water was shallower than they thought, and she stuck about 80 yards out. Some lighters were put to connect with the shore and we began running along them to get down to the beach. I can’t tell you how many were killed and drowned, but the place was a regular death trap’

Captain Guy Nightingale, 1st Battalion Royal Munster Fusiliers

Such was the intensity of fire from the defenders that it was decided during the day that no further attempts should be made to land troops from the ship until the cover of darkness. Despite strong Turkish opposition the Allies managed to land sufficient troops to establish a beach-head at Cape Helles and ANZAC Cove.

Much has been written about the landings at V Beach and arguments have continued regarding the actual number of casualties for the Royal Dublin and Munster Fusiliers on 25 April. There are differences in statistics of the exact numbers killed between the Commonwealth War Graves Commission and the Soldiers Died Records. Current research would show that the reports of casualties were released in such a way as to down play the actual facts. Notwithstanding these casualties (including wounded personnel) sustained by the two battalions were sufficient enough for both battalions to combine into an ad hoc battalion nicknamed the ‘Dubsters’ for the period 30 April- 19 May 1915.

On 30 April, the respective strengths of the battalions were as follows: 1st Battalion Royal Munster Fusiliers: 12 officers, 596 other ranks; 1st Battalion Royal Dublin Fusiliers: 1 officer, 374 other ranks; from the normal strength per battalion of 26 officers and (approximately) 1,000 other ranks.

My research into the Irish at Gallipoli shows the following fatalities recorded for 25 April (Fig. A). They also show, particularly with regards to the Royal Dublin Fusiliers, the breakdown in the command structure due to officer and NCO casualties.

Fig. A.

Killed in Action 25 April Royal Munster Fusiliers/Royal Dublin Fusiliers

| Regiment | Officers | NCOs | Privates | Total |

| Munster Fusiliers | 43 | 57 | ||

| Dublin Fusiliers | 52 | 65 |

Irish fatalities in the initial landings on 25 April, were not restricted to just these two battalions. Approximately 19 Irish born were killed during the landings at ANZAC Cove while serving with the ANZACs and approximately another 19 Irishmen were killed while serving with other British Regiments such as the Hampshire Regiment, Lancashire Fusiliers and the Essex Regiment.

As with all statistics, there is a personal story behind them. For some families the soldier killed at Gallipoli would be the first loss during the war for that family, while for some families there would be double tragedies suffered by them during the initial landings at Gallipoli. The Mallaghan family from Newry, Co. Down would receive word that their two sons who served in 1st Battalion Royal Dublin Fusiliers had been killed at V Beach. 10372 Private Samuel Mallaghan (aged 21) was reported as killed in action on 25 April, and his brother, 10741 Private John Mallaghan (aged 19) was reported as killed in action on April 30th. The Smyth family from Glendermott, Derry would also lose two sons. 10696 Private Samuel Smyth (aged 28) and 10058 Lance Corporal William John Smyth (aged 31) were both killed in action on 25 April.

Early in the land campaign it was realised that the hoped for breakthrough and success of the Gallipoli Campaign had been denied to the Allies by the tenacity of the Turkish defenders. The stalemate and trench warfare of the Western Front had all too painfully set in at Gallipoli. Success was measured in feet and yards, the Allies never advanced more than three miles up the Peninsula, with opposing trenches no more than 15 feet away from each other in some case.

The Gallipoli Campaign – May and June

Throughout May and June 1915, the Royal Munster Fusiliers and Royal Dublin Fusiliers, though badly mauled, would continue to serve in the frontline at Gallipoli. They would, alongside the Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers (who also sustained heavy casualties), took part in the second and third battles of Krithia and sustain further casualties and lost many of their pre-war regular soldiers with whom they had started operations.

The battalion history of 1st Battalion Royal Dublin Fusiliers (Neil’s Bluecaps Volume II), describes the ‘scanty reinforcements’ that reached the battalion at Helles, comprising 3 officers (Captains C.B. Riccard, W.F. Stirling and Adrian Taylor), 1 Sergeant, 2 Corporals and 43 Privates from the battalion reserves at Mudros, along with another officer from the 3rd Battalion and 4 officers from the 9th Battalion Somerset Light Infantry. A total reinforcement of just 54 officers and men. After receiving these meagre reinforcements, the 1st Battalion was reconstituted as a separate unit on 19 May.

During the Battle for Gully Ravine (Third Krithia) the Dublin Fusiliers suffered enormous casualties when on 28-29 June, they lost approximately 236 officers and men killed, wounded and missing. The old regular army battalions were being bled to death at Gallipoli and the black ribbons were being hung on doors all across Ireland. The true reality of the war was being brought home to these families and the Irish as a nation.

By mid-June 1915, plans were made for large scale re-enforcements to the MEF and a new offensive was planned for August to break the dead-lock. The Irish involvement in the new campaign would increase with the inclusion of the 10th (Irish) Division, which would include Service Battalions of almost all the existing Irish regular regiments. The 10th (Irish) would be the first of the three raised divisions in Ireland which would see active service during the war, and its use and treatment would affect Irish attitudes to the war much deeper than any other Irish units engagement.

The 29th Division, the only regular division in the MEF, remained at Gallipoli until January 1916. It was used as the ‘Fire Brigade’ Division throughout the campaign and during the August offensive served for a period of time at Suvla Bay before returning to serve at Helles until the final evacuation. It earned the title ‘The Incomparable 29th’ due to its service. The 10th (Irish) Division and its role in the August campaign will be discussed in Part 2.

There is more to be told about the Irish at Gallipoli, the Irish graves that stretch from the Gallipoli Peninsula, through Egypt, Malta, the depths of the Mediterranean, Gibraltar, and across the UK and Ireland have their own story to tell about the effect they had on Ireland and it’s people and should no longer be considered as ‘Lonely graves by Suvla’s waves’.

Mal Murray is a former member of the Irish Defence Forces. He is currently the Gallipoli Associations Forum Manager. For more information see: www.gallipoli-association.org